“The dignity of the Yoreme people begins with speaking our language.”

The dignity of the Yoreme people begins by speaking our language

Antolín Vázquez is recognized by the Mexican government for his work defending his culture // The award is for my community; I owe it all

, he asserts in an interview

▲ Antolín Vázquez Valenzuela says the recognition doesn't mean his work is over. Photo by Cristina Gómez

Cristina Gómez Lima

Correspondent

La Jornada Newspaper, Monday, July 21, 2025, p. 2

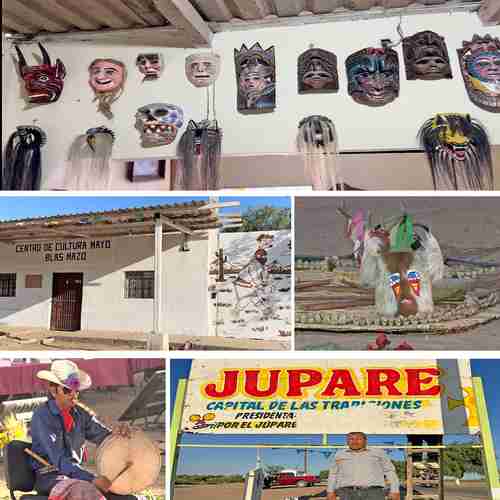

Huatabampo, Sonora, nestled among the agricultural valleys of southern Sonora, in the indigenous community of El Júpare, lives Antolín Vázquez Valenzuela, a man of measured words, a fertile memory, and a firm voice when speaking of his people. At 61, he has been recognized with the 2024 National Prize for Arts and Literature in the field of Popular Arts and Traditions for his tireless work defending and disseminating Yoreme-Mayo culture.

For him, the award isn't an individual recognition, but a collective one. "The prize is for my community, for my people. I owe them everything

," he states without hesitation.

Vázquez Valenzuela was born in Navojoa, but the day after his birth he was taken to El Júpare, an indigenous community located in the municipality of Huatabampo, where he grew up under the guidance of his parents, agricultural laborers, and his grandmother, Cornelia, a midwife and proud speaker of Yoremnokki, the native language of her people.

My great-aunt lived with us and never stopped speaking to us in her language. Thanks to her, we never forgot her. She nourished us with her words, her affection, and her scolding in Yoreme

, recalls Vázquez Valenzuela.

The tenth of 11 siblings, he spent his childhood picking cotton and harvesting sesame seeds, where he also learned the value of tradition. At just seven years old, he was already working in the fields, but his spirit was nourished by the ceremonies, dances, and songs he heard around him.

My father took us to school and instilled in us respect for our community. My mother, Virginia, dreamed of learning to read. Although she suffered discrimination for speaking her language, she never stopped communicating with my father in it. That left a lasting impression on us

, she shared in an interview with La Jornada.

In 1982, the young Yoreme, with an unfinished bachelor's degree in sociology, was invited to an intensive course for indigenous cultural promoters in Toluca. "I was with my father harvesting sesame seeds when they came looking for me. That course was a revolutionary seed in me. It made me deeply appreciate who we are."

For 35 years, Vázquez Valenzuela worked at the Regional Unit of Popular and Indigenous Cultures of Sonora, where he carried out extensive work rescuing and promoting the Yoreme oral tradition. He is the co-author of the book "Words of the Yoreme World: Traditional Tales of the Mayo People" and the founder of the Blas Mazo Cultural Center in El Júpare, as well as the Francisco Mumulmea Zazueta Mayo Cultural Center in Buaysiacobe, Etchojoa.

Her work has been a constant response to the risk of disappearing indigenous languages, such as Yoremnokki, which is currently spoken fluently by barely 30 percent of the community settled in southern Sonora. The most painful thing is that young people no longer understand the message of the songs in their language. They sing them, but they don't understand them. "The profound sense of our identity is lost

," she lamented.

For Antolín Vázquez, language is the basis for the dignity of Indigenous peoples. It is the language with which our ancestors were forged, the one with which we name nature, the body, the spirit. Oral tradition is like a breast: it suckles, it nourishes. If it doesn't, it doesn't survive

.

Despite the national recognition, he insists his work is not over. "I've retired from the institution, but not from my community. I will continue promoting our culture until the day I close my eyes, because my passion for serving, fostering, and dignifying our culture will always be there

."

Living celebrations

The Júpare keep their religious ceremonies alive through a traditional organizational system passed down from generation to generation. The patron saint festivals in honor of the Holy Trinity, the Deer Dance, Lent, and the presence of up to 200 Pharisees each year are expressions of a syncretic worldview that intertwines ancestral spirituality with elements of Catholicism brought by Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries. Religious syncretism has given us cohesion. We also feel Yoreme in our faith, and that distinguishes us as a tribe

.

In El Júpare, where hundreds of families gather each year for community celebrations, there is a sense of living resistance to being forgotten. "We are a people who resist globalization

," he says with conviction. "That's why it's important that our customs and traditions be respected. Without language and traditions, there is no identity

."

Antolín Vázquez doesn't shy away from challenges. Migration, linguistic displacement, racism, internal political fragmentation, and the impact of drug trafficking have left their mark on his community. Some young people study, but then get lost. Many go to the border, but there they form groups so they won't forget their festivals

, he emphasized, mentioning the group of Yoreme indigenous people who have migrated to Nogales, on the border between Mexico and the United States, where they also celebrate their traditional dances and prayers.

In the talk, she shares that one of her greatest prides is seeing her eldest daughter, Trinidad, become the first female president of the traditional position in El Júpare. She held the position for three years. It was a very important moment for our family. A sign that traditions continue, that there is hope

.

Upon receiving the news of the National Prize, Vázquez Valenzuela was surprised. The head of the Fine Arts Department called me. I was astonished. When did this happen?

He thanks those who have supported him along the way: his family, teachers, the elders in his community, and his colleagues.

The cultural promoter closes the conversation with an invitation: Come and learn about the traditional life of Indigenous peoples. We are a large community of spirit and heart. We refuse to disappear. We will continue to be here, dancing, singing, speaking our language, and caring for our roots

.

Antolín Vázquez Valenzuela's career transcends institutional recognition. While national recognition is being prepared to be presented in Mexico City, this Yoreme man continues his work from his community, as always: with his eyes fixed on his roots, his heart set on the land, and his firm voice reiterating: The dignity of Indigenous culture begins with speaking our language and living our traditions with pride.

National Awards

If traditions continue, there is hope

▲ Photo by Cristina Gómez Lima

La Jornada Newspaper, Monday, July 21, 2025, p. 3

In southern Sonora lies the indigenous community of El Júpare, home to Antolín Vázquez Valenzuela, winner of the 2024 National Arts and Literature Award in the category of Popular Arts and Traditions for his work defending and disseminating Yoreme-Mayo culture. In an interview with La Jornada, he asserts that his struggle responds to the risk of indigenous languages disappearing, such as Yoremnokki, which is currently spoken fluently by 30 percent of the community in southern Sonora. He notes that the award does not end his efforts, as for him, the best way to dignify his culture is to speak the native language. We are a people of great spirit and heart. We refuse to disappear. We will continue here, dancing, singing, and caring for our roots

.

jornada